“There was a time, when I first found out I was pregnant with twins, that I saw only a state of conflict. When I looked at theater and parenthood, I saw only war, competing loyalties, and I thought my writing life was over. There were times when it felt as though my children were annihilating me (truly you have not lived until you have changed one baby’s diaper while another baby quietly vomits on your shin), and finally I came to the thought, All right, then, annihilate me; that other self was a fiction anyhow. And then I could breathe. I could investigate the pauses.”

-Sarah Ruhl, introduction to 100 Essays I Don’t Have Time to Write

In 2017 Parents in Chicago Theatre published a report titled Barriers to Work for Parents in Chicago Theatre, which investigated the effect of parenthood on the careers of a wide variety of Chicago theatre artists. Low pay, scheduling, the high cost of childcare and the storefront theatre culture all contribute to stalled careers and stagnant incomes for parents. A follow-up report attempts to capture a group of parents whose experiences weren’t captured: the ones who had left the industry altogether. A second survey reached out to the parents for whom the barriers were insurmountable, and what the Chicago theatre industry has lost in terms of education and experience.

The 2018 survey asked people who took an extended break or stopped working in the Chicago theatre industry after becoming parents about their experiences. Most of them (85%) still have at least one child below school age, which is the time where the childcare responsibilities are usually the greatest. All but one of them are female.

Who are the Lost Voices of Chicago Theatre?

This survey captured a snapshot of the careers of a group of parents who took a break from their work in theatre as actors, directors, writers, designers, technicians and administrators. About half are currently taking a break from working in theatre, either to be a full-time parent or to work in a different industry. The other half returned to working in theatre after taking a break with their child(ren), but none are working full-time in theatre. Some of those also work a day job.

Of the approximately ⅓ of respondents who are working outside theatre, almost all are working full-time. The two reasons cited the most often were higher pay was more and a schedule more compatible with parenting young children. This is consistent with the findings in last year’s report that scheduling, low pay and the cost of childcare are the greatest barriers for parents working in theatre.

Education and Experience

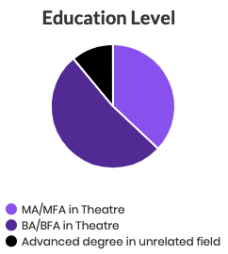

The education level of most respondents is very high. Almost all have at least one degree in theatre, and about a third have a masters degree in theatre. This is the same for those who left the industry and those who are currently taking a break and intend to return. Education doesn’t seem to be a factor in whether someone will leave the theatre industry after becoming a parent. A significant number of people in Chicago theatre have made a huge investment in their education, yet are finding it impossible to maintain a career in their chosen profession since becoming a parent. This also means that there is a wealth of knowledge and expertise that the industry is missing out on by not supporting parents.

The education level of most respondents is very high. Almost all have at least one degree in theatre, and about a third have a masters degree in theatre. This is the same for those who left the industry and those who are currently taking a break and intend to return. Education doesn’t seem to be a factor in whether someone will leave the theatre industry after becoming a parent. A significant number of people in Chicago theatre have made a huge investment in their education, yet are finding it impossible to maintain a career in their chosen profession since becoming a parent. This also means that there is a wealth of knowledge and expertise that the industry is missing out on by not supporting parents.

“I’ve given up trying to get a job in theatre and view my “day job” as a career.”

– Theatre admin and dramaturg with an MFA and 6-10 years of experience, mother of a two-year-old

Most of the parents surveyed also had a significant level of experience – an average of 13 years. More than half of respondents have over 15 years of experience. There is of course some attrition in the theatre industry of people who study and “pay their dues” working in theatre, but find it an unsustainable long-term career. However, the parents questioned in this survey pointed to clear factors related to becoming parents that are keeping them from returning to working in theatre, even though they want to.

“I just needed to get on stage. It’s been four years. I’m bleeding for stage time.”

– Actor with over 15 years of experience, mother of two young children

To Return or Not to Return?

Respondents took breaks for anywhere from eight weeks to eight years after the birth of a child. The average break for parents was 1.5 years. Those with more than one child may have gone back to work after their first child, but found it more difficult with two children. Many elements factored into these decisions, but there were four that were reported most often: The incompatibility of freelancing and theatre schedules with parenting, the high cost of childcare – especially relative to the low pay in theatre – and the desire to be the child’s primary caregiver.

All of these factors other than the last one can be mitigated by theatre employers. When asked what the theatre industry could do to make returning to work more achievable for parents, respondents had a lot to say. Overwhelmingly, the accommodation respondents most craved was childcare. There are many forms this can take depending on the size and budget of the theatre and the needs of the parent artist. Some popular ideas were child-friendly auditions, on-site childcare or additional stipends for childcare during technical rehearsals. Respondents also said that more predictable schedules, higher pay and a culture that is more understanding of the needs of parents would go a long way to making returning to work possible.

All of these factors other than the last one can be mitigated by theatre employers. When asked what the theatre industry could do to make returning to work more achievable for parents, respondents had a lot to say. Overwhelmingly, the accommodation respondents most craved was childcare. There are many forms this can take depending on the size and budget of the theatre and the needs of the parent artist. Some popular ideas were child-friendly auditions, on-site childcare or additional stipends for childcare during technical rehearsals. Respondents also said that more predictable schedules, higher pay and a culture that is more understanding of the needs of parents would go a long way to making returning to work possible.

“It’s like trying to get back on a moving bus. Especially when my first child was born, I saw lots of my peers making great career strides and it was quite frustrating. It felt like a career leap backward.”

– Technician with over 20 years of experience, parent of two

Other elements factored in to parent artists choosing to work outside of theatre beyond higher pay and better hours: Health benefits and parental leave. Only about 15% of respondents received health insurance through their theatre employer or union while they were expecting a child. About half were covered by their partner’s insurance and the rest through a day job or the Affordable Care Act. Only one respondent received any kind of paid parental leave from a theatre employer, and that was through short-term disability insurance. Parent artists have less incentive to return to work in an industry that can’t or doesn’t provide these essential benefits. As freelancers, many theatre workers don’t even qualify for unpaid FMLA leave, as that requires one to work for at least a year for one company that has 50 or more employees. This excludes almost every theatre company in Chicago.

“Theatre operates on the assumption that someone else will bear the financial burden of our lives.”

-Actor and AEA member, mother of two young children

Career Satisfaction for Parents

Despite many of them having found careers outside of the theatre industry that pay more or have a more flexible schedule, 77% of those taking a break from theatre plan to go back at some point.

When asked about career satisfaction, respondents had mixed feelings. Many said that they have to choose their projects more carefully or that they wish they could work more in theatre, but find balancing work and parenting difficult. Only 15% of respondents who have left theatre report being happy in their career trajectory. Those who have a positive view of their current trajectory often noted that it was because their expectations had changed. Without a viable pathway back into the industry, these decades of experience will be lost to Chicago’s theatre industry.

“I enjoy working and providing for my family, and I love being with my family. When the time is right, I know I will jump back in because art is what I love.”

-Director with master’s degree, mother of two

Industry Change

Our partners at the Parent Artist Advocacy League (PAAL) are compiling a Best Practices Handbook full of interviews, case studies and resources for theatre organizations who want to be inclusive of parent artists in their organization or bring in parent artists who may have taken a break.

I also wrote a case study of a parent-friendly production at Rivendell Theatre Ensemble that I wrote for HowlRound titled Radical Inclusion of Parent Artists.

Why Do We Need Parent Artists?

The final question I asked is, how has becoming a parent made you a better artist, employee or collaborator? Here are the replies: